When Fidel Castro enacted the First Urban Reform Law in Cuba in 1960, the revolutionary government presented it as a heroic act. The measure cut rents by 50% overnight, claiming it was a matter of social justice for working families.

However, what initially appeared to be a victory for the tenants ultimately marked the beginning of a housing tragedy that continues to persist.

In Spain, some tenant movements and unions are demanding a 50% reduction in rents, raising the question: How is it possible that, with Cuba's clear precedent, this populist solution is still viewed as viable?

In Cuba, the First Urban Reform Law not only halved rental prices but also marked the beginning of a massive expropriation process.

Real estate properties were seized from their rightful owners and transferred to state control.

This act, framed as a strike against "speculators" and "exploiting rich," stripped thousands of families of their assets and effectively eliminated the real estate market.

With no possibility of legally buying or selling homes, Cuba's housing economy was brought to a standstill.

The expropriated homes, which previously provided income for their owners and housed families in decent conditions, have transitioned to a state allocation system that quickly became inefficient and corrupt.

The original owners were forgotten, and the new occupants, mostly tenants, found themselves caught in a cycle of decay: without incentives or resources for maintenance, the houses and buildings began to literally crumble.

With a state unable to meet demand and lacking a market to encourage new construction, the country has been plunged into a chronic housing crisis, a reflection of the failure of government policies of expropriation and absolute control.

Cuba: A Housing Disaster

Fidel Castro's action had devastating long-term effects.

The reduction in rents removed the incentive for landlords to maintain, repair, or invest in properties.

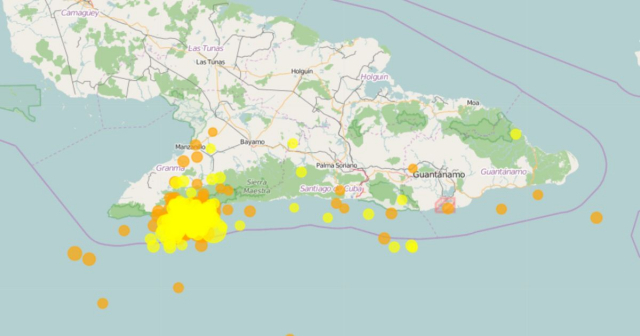

Over time, Cuba's housing stock has deteriorated alarmingly. Today, more than 39% of homes in Cuba are in poor condition or at risk of collapse, and millions of Cubans live in overcrowded conditions, sharing small spaces with up to four generations under one roof.

Worse still, the policy of expropriation and state control has stifled the development of new housing.

With a non-existent real estate market and a government unable to meet demand, the housing crisis in Cuba has become a symbol of the failure of the centralized economic model.

The idea of "social justice" ultimately condemned Cubans to decades of precarious living conditions and housing despair.

Spain: Adéjà vuIdeological?

In Spain, unions such as the Tenants of Catalonia are demanding a 50% reduction in rental prices, arguing that current prices are unsustainable. While it is true that the real estate market in Spain faces serious challenges, implementing such a drastic measure risks replicating the same mistakes as in Cuba.

One of the main issues is the scarcity of available housing, exacerbated by complex bureaucratic obstacles and taxes that delay or increase the cost of construction. This is compounded by a troubling lack of urbanized land available for new developments, which limits the ability to increase the housing supply at a pace that meets the growing demand in major cities and metropolitan areas.

The lack of a solid public housing sector is another key factor putting pressure on the market. For decades, Spain has invested little in social housing, leaving the most vulnerable sectors at the mercy of the private market. Unlike other European countries with larger reserves of public housing, the Spanish state cannot provide a solid alternative for families affected by high rental prices.

On the other hand, the legal insecurity faced by landlords contributes to worsening the crisis. Many property owners prefer to withdraw their homes from the residential rental market, concerned about issues such as unpaid rents, lengthy legal processes for evictions, and the risk of illegal occupations. Rather than confronting these uncertainties, they choose to convert their properties into tourist accommodations or leave them vacant, further reducing the available supply for residential rentals.

Imposing a measure like the forced reduction of rents by decree, without addressing these underlying issues, will only exacerbate the situation. Similar to the case in Cuba, discouraging private investment in the real estate market and failing to provide viable alternatives through comprehensive public policies could create a vicious cycle: reduced supply, increased speculation, and a housing stock that continues to deteriorate. Instead of applying simplistic solutions, Spain needs a balanced approach that encourages construction, protects both property owners and tenants, and promotes the establishment of a robust public housing sector.

If the government intervenes so aggressively, investors will seek more stable markets, which will worsen the supply crisis and increase issues related to access to housing.

The result? A worsening of the housing stock, a more restricted market, and increased speculation.

The Price of Populism

The case of Cuba demonstrates that populist measures that do not address the structural roots of the housing problem are a recipe for disaster. Imitating Fidel Castro's policies under the guise of social justice overlooks the collateral costs of such decisions.

What may seem like an immediate solution to ease the burden of rents would only deepen the housing crisis in the long run.

Spain, a market economy, cannot afford to follow the path of a failed model like that of Cuba.

Instead of repeating historical mistakes, Spain must find sustainable solutions that promote the development of the real estate market, protect vulnerable tenants, and ensure access to decent housing.

In housing populism, as in history, easy solutions are almost always the most expensive.

Filed under:

Opinion article: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoint of CiberCuba.