The long and anguishing battle of the family of the Grand Master Guillermo García (1953-1990) for rescuing the amount of a prize withheld from the eminent Cuban chess player in the United States for 34 years, finally culminated this week with the triumph of his only heir.

After a tough legal dispute and the recent resumption of Western Union operations to send remittances to Cuba, Antonio García Labrada, son of the chess player, will have access to an estate of $10,413.84 dollars that remained frozen in a New York bank due to the embargo, federal regulations for inheritance transactions and financial barriers imposed by Donald Trump's administration since November 2020 .

With the approval of the Treasury Department and the pilot program activation launched this week by Western Union, ends a tense game of the García Labrada family for the recovery of the amount awarded to the chess player as award for his performance at the New York Open Tournament in 1988, when he placed second, behind the Ukrainian GM Vasily Ivanchuk.

But the embargo restrictions They prevented him from collecting it for residing in Cuba, included in the list of countries sponsoring terrorism since 1982, and García had to return to Havana with the runner-up medal and empty hands, waiting for a modification of the rules on the political board.

The prize for Guillermito - as the player was popularly known - was then $10,000 dollars, but the total accumulated in the account during the elapsed time amounted to $16,468.89 dollars. Of that amount, the lawyers involved in the case, José I. Valdés, in Miami, and William T. Shepard, in New York, they collected about $6,000 in legal fees and for administration of the estate, and the remaining money corresponds to García Labrada, 38 years old and resident in Havana.

“It has been a real odyssey to get to the end of this case,” he told CyberCuba the lawyer José I. Valdés, who was in charge of representing García Labrada in the United States for 10 years. “No process for claiming inheritances from residents in Cuba has been as long and demanding as this one.”

Valdés belongs to a select group of American lawyers who have a special license from the Foreign Assets Control Office (OFAC) of the Department of the Treasury to represent the rights of Cuban citizens with inheritances in the United States.

The granting and collection of hereditary assets to Cubans residing on the island was authorized by the administration of George W. Bush in 2003. Since then, OFAC regulated that Cuban heirs can receive through remittances the money awarded by US courts and retained in the Blocked Cuban Accounts (CBA), also known as “frozen accounts.”

It is estimated that more than $500 million have been sent to heirs in Cuba using this legal mechanism. OFAC has not revealed an exact number of operations carried out in this modality since this option was opened two decades ago.

Thus, in 2013, González Labrada began processing the frozen account in his father's name in the Popular Bank of Puerto Rico, at the Manhattan branch.

Why was the chess player's account placed there? The historian and journalist Miguel Angel Sanchez, author of the biography Capablanca, legend and reality (2015), recalls the reasons that Cuban-American lawyer Eddy López had for recommending this step to Guillermito after his successful performance in the New York tournament.

The restrictions of the embargo prevented García from staying in the United States or going to reside in a third country, but that was not in the Villa Clara trebejista's plans. The ban shocked the chess world and the prestigious magazine New in Chess He even described it as a “truly abominable” case of political interference in chess affairs.

“López was a good friend of the tournament director, José Cucci, and upon learning that Guillermito could not collect the money, they decided between them that the money would be retained in the Banco Popular de Puerto Rico (BPPR), of which López was an associate attorney. "Sanchez told CyberCuba.

According to the historian, lawyer López considered putting the money in a non-aggressive investment fund, but finally decided on a regular account with interest, to take less risk for everything it meant for the chess player.

“And I think he was very clear in the decision,” said Sánchez.

But the procedures with the BPPR became more complicated than expected.

The frozen account of the deceased had to be transferred to a similar one created in the name of the claimant in a US bank, which carried out blocked account transactions, among which Professional Bank and Coconut Grove Bank, both in Miami, could be selected, but the BPPR demanded other additional requirements.

In June 2014, a Cuban court issued the declaration of heirs over the assets of Guillermo García González, which designated García Labrada as the sole beneficiary. The chess player's widow, Ada María Labrada, also residing in Havana with his son, had renounced his hereditary rights.

Following that judicial decision, OFAC authorized the creation of the blocked account for the owner Antonio García Labrada in November 2015, but the BPPR raised the bar on its demands and determined that the case should be transferred to the Court of Inheritances and Guardianships of New York. to declare the award final and be able to issue the check payable.

The issue was even more complicated, since it was necessary to arrange for a lawyer licensed in the state of New York and willing to charge low fees so as not to affect the amount destined for García Labrada.

“It was truly providential to find Shepard willing to do this and his generosity should be appreciated so that this process could be unblocked,” said Valdés, who also reduced the cost of his fees.

The legal entanglement did not stop there. The New York court requested certified statements that Valdés represented the García Labrada family in the United States and was the executor of the estate, as well as a letter from the funeral home that hosted the chess player's funeral, confirming that no money was owed for that service fulfilled.

After completing the certification procedures in the United States embassy in Havana, the original documents arrived at the New York court.

The litigation was resolved amid the scourge of COVID-19, but the New York court's certification to authorize the transfer of the frozen account was delayed due to the closure of government institutions due to the pandemic.

When everything was ready in December 2020, the impediment to sending the money to its recipient was greater. Since November 26 of that year, President Trump had sanctioned the state-owned FINCIMEX for its dependence on the Cuban military, which led to the cancellation of Western Union operations in Cuba.

More than 300 cases were left without being able to collect their estates in Cuba since the paralysis decreed by Trump to the operations of the more than 400 Western Union branches, spread throughout the country.

“Guillermito's family really became terrible... There were so many obstacles that they don't seem credible,” commented Valdés.

The OFAC authorization to send inheritances was granted to Western Union and is not governed by the general formulation of family remittances, but rather responds to a separate category and can only be sent by the assigned attorneys.

That is why the flexibility stipulated by the administration of Joe Biden to process family remittances to Cuba did not cover shipments of hereditary assets.

Although the regulations do not prohibit sending estates by entities such as VaCuba and Cubamax, authorized this year by OFAC to process remittances through the state-owned Orbit, lawyers prefer not to take risks with companies that do not have a guarantee from the federal government and do not have support from US banking institutions.

Additionally, VaCuba and Cubamax operations do not handle large volumes per shipment, making inheritance transactions difficult. At first, only $300 dollars could be sent quarterly, but since 2009, Barack Obama's administration eliminated the limits on the amount, at a rate of $5,000 dollars for each transaction, but with the possibility of billing more than one daily.

The restrictions on remittance shipments to Cuba applied by the Trump government Since 2019, they have not affected inheritance procedures.

Since last November, when the OFAC granted a license to VaCuba to operate remittances to the island, inheritance lawyers were trying to negotiate a differentiated rate for their shipments, considering that the volume of the operations deserved a lower tax. But the process was bogged down waiting for a decision from the Cuban Ministry of Justice.

In that wait, Western Union reopened its operations and finally cleared up the intricate skein of the family inheritance of the famous chess player, who died in a car accident at the height of his career.

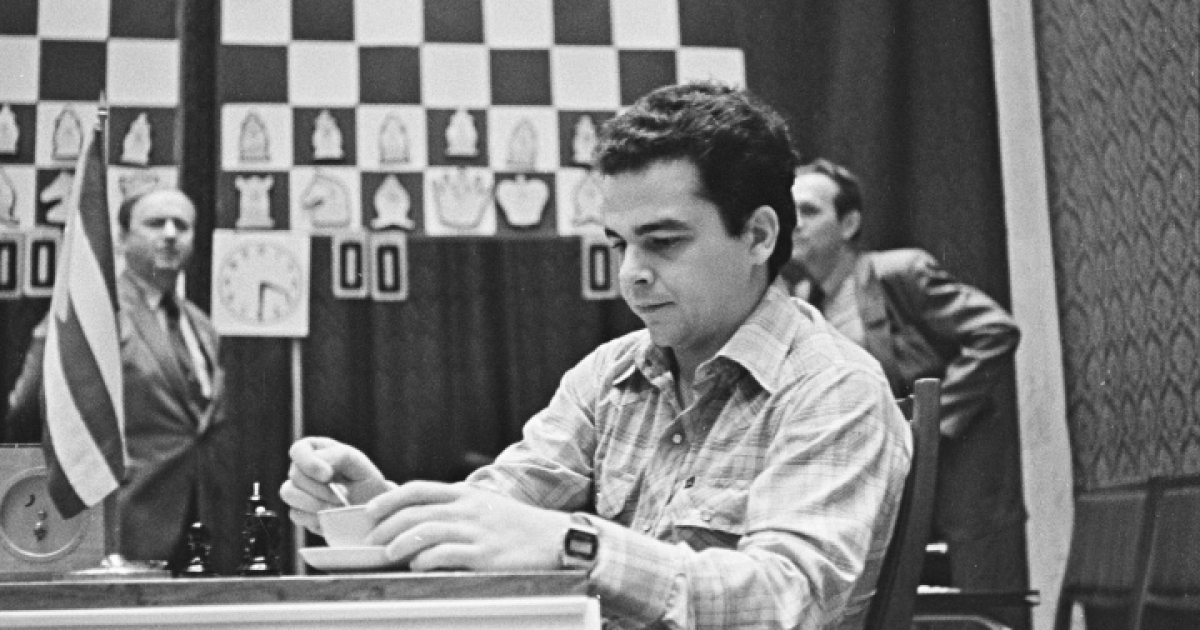

Guillermito was recognized as the most talented Cuban player after the genius José Raúl Capablanca (1888-1942), accumulating 2,535 ELO points.

At the time of his tragic death, the idol of Santa Clara had linked an impressive chain of international triumphs for Cuban chess. He was a three-time national champion, won two Capablanca in Memoriam tournaments, represented Cuba in seven Chess Olympiads and completed his Grandmaster title in 1976, at only 22 years old.

What do you think?

SEE COMMENTS (3)Filed in: