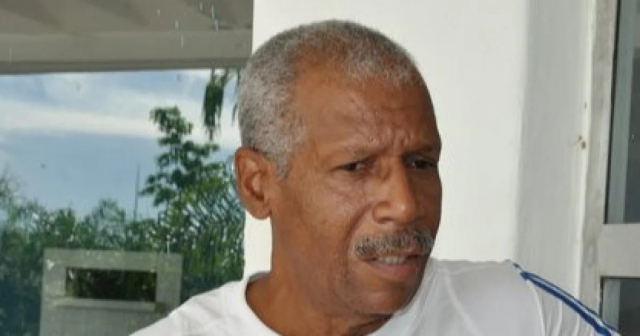

"When a friend leaves," the anthem by Argentine singer-songwriter Alberto Cortez, certainly describes the truth experienced when someone like Hermes Ramírez says goodbye. Unfortunately, the Olympic silver medalist from Mexico '68 could not overcome the race of his existence this time and lost the final sprint… not without a fight!

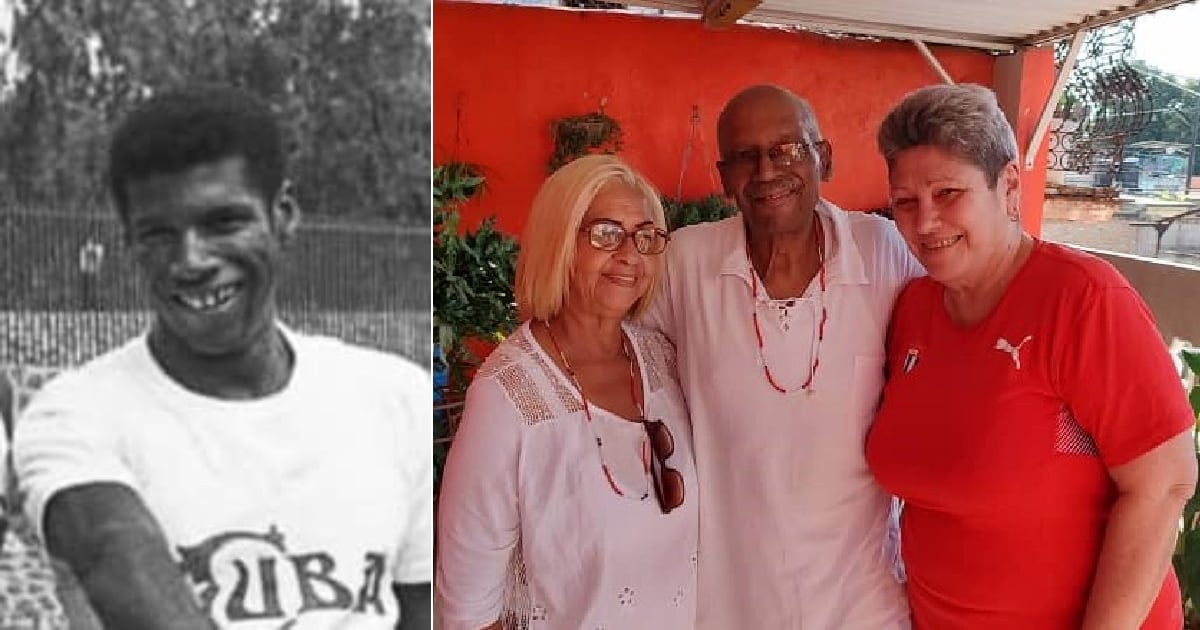

Born in Guantánamo 76 years ago, Hermes belongs to that initial generation of track and field athletes that included Enrique Figuerola, Miguelina Cobián, Pablo Montes, Juan Morales, and Marlene Elejalde, among others; that generation that only thought about competing and winning for the flag with no material interest, that dreamer generation.

Hermes was one of my most eloquent and intelligent interviewees; he always had a pleasant way of speaking and acting. I believe remembering some of our exchanges, which were more like brotherly chats, honors him.

Many times I talked about the unity that existed in his time: "Life changes, the situations, the environment surrounding the sport now are not the same. In my time, to give you an example, once Professor Riverí - do you remember him? The one who guided the discus throwers Maritza Martén and Luis Mariano Delís - approached me to point out that the starting block of one of my runners was too high, being I the coach."

"Do you understand me? A pitching coach noticed something that I didn't see. He helped me! That's how we were, one big family. And now...?"

And, of course, talking to Hermes and not recalling his precious sporting life was impossible. How does this legend of Cuban athletics begin in the athletic hustle?

“It is true that I was born in Guantánamo, but I lived in Havana from the age of four, and at 12, when I was a scholarship student in Tarará, they came to do some LPV tests (you know, Ready to Overcome), and in the 100-meter race, with sneakers and in the middle of the street, on cement, I recorded 12 flat. The following year, in a scholarship competition at the Pedro Marrero stadium, running on clay, I came in second with 11.8, with manual timing, of course. The first was Duquesne, who was already in the Technological Institute; I was just a kid. That’s how I competed in what would be the first National School Games in 1963. At that time, I was studying in Barlovento, under the guidance of the prestigious coach José Cheo Salazar. In the hundred meters, I marked 11 flat, and in the 200 meters, 23.2.”

What happened after the first National Games?

"I was studying at the Basic Secondary School Lazo de la Vega, formerly Ursulinas de Miramar, when I was contacted by Rolando Gregorio Lavastida, who began officially training me in 1964. During that time, I competed in the second School Games and won again in the 100 and 200 meters, and I came second in the 4x100. And then came one of the most bitter moments of my life."

"While the school event was taking place, the qualifiers for the Tokyo Olympic Games were happening. To participate, the minimum mark in the 100 meters was 10 seconds and 4 tenths, and let me tell you that I, at the age of 16, achieved it along with Manuel Montalvo."

"You can imagine the joy that overwhelmed me, but - why must there always be a but? - the then president of INDER, José Llanusa, decided that my youth was a handicap and prevented my attendance, depriving me of the opportunity to accumulate four Olympics in my résumé."

"Nevertheless, I was not intimidated and in 1965 I was the best youth player at the national level across all sports, which secured my place on the national team, where I remained for 12 years between 1964 and 1976."

As we can see, the life of Hermes Ramírez is worth telling and, most importantly, that it be known and respected by all those who are starting out in Cuban athletics. Two Central American and Caribbean Games: San Juan 66 and Panama 70; three Pan American Games: Winnipeg 67, Cali 71, and Mexico 75, as well as three Olympic Games: Mexico 68, Munich 72, and Montreal 76, attest to an impressive legacy in times when there were no World Championships or Diamond Leagues.

In Mexico 68, Hermes tied the then Olympic record for the hundred meters with a time of 10 flat in the quarterfinals, although he could not advance beyond the semifinals due to a sticky fever of 40 degrees that incapacitated him. However, he was able to run in the relays, and in the final, with a time of 38 seconds and 300 hundredths, Hermes Ramírez, Juan Morales, Pablo Montes, and Enrique Figuerola finished on the podium behind the United States (38.200). I can say that what Hermes liked most was to reminisce about that race.

"We were the breakout team of the season, having broken the world record in the semifinals with a time of 38 seconds and 75 hundredths. We were led by the seasoned Lázaro Betancourt, who along with Irolán and the Polish Porchovoski handled the strategy to face the challenge: relay team members, who would run each segment, prior training..."

"We were six: Enrique Figuerola, Pablo Montes, Bárbaro Bandomo, Félix Urgellés, Juan Morales, and me. At the games headquarters, it was decided that the last man would be Enrique and that Bandomo, a strong sprinter with excellent times of 10.2 and 10.3 and a flying speed of 9.05, would not be in the relay. According to many, he was the best option. History weighed in, although we were never frustrated."

"Frustrated, no! We won a medal; that was the goal, but... we could have reached the top of that podium. We set a national record, 38 seconds and 40 hundredths, which stood until Barcelona '92: 24 years! But we could have won."

Hermes Ramírez was part of the national team for twelve years, during which he set three records of 10 flat in meetings held in Zurich '69 and Prague '71 and '72; a time of 20 seconds and 83 hundredths in the 200 meters in Warsaw '72, and 38.40 in the short relay in Mexico '68.

Once retired from active sports, Hermes became a coach and always felt the sorrow of witnessing the decline of speed in Cuban athletics.

"Speed is the result of a good foundation of general endurance, special endurance. In my time, we had to run up to 400 meters in training. I remember one day Irolán showed up and said in his usual friendly manner: 'Today you have 10,000 to run'... And I had to run them. Tell any of the kids to do it now, and you'll see their response: 'You're crazy!' That's not how you can build a solid foundation for sprinters."

Hermes Ramírez has left us, the one who took pride in having three children, four grandchildren, three great-grandchildren, plus the descendants of his beloved wife Mercedes; the one who loved his sport and always respected and wished the best for the Cuban athlete, wherever he was.

I had the honor of welcoming him to my home days before the start of the Paris Olympic Games, and among other things, he predicted the three Cubans on the podium in the triple jump competing for other flags, the pressure that the triple jumpers might face, and the almost certainty that Cuban athletics would leave without medals.

He spoke about Mijaín López standing up for Cuban sports and that women's judo, without Professor Veitía, would not achieve anything, as well as the noticeable decline of boxing.

Faithful lover of Cuban sports, passionate about its athletics, rest in peace dear Hermes, brother and friend for so many years.

What do you think?

COMMENTFiled under: