Related videos:

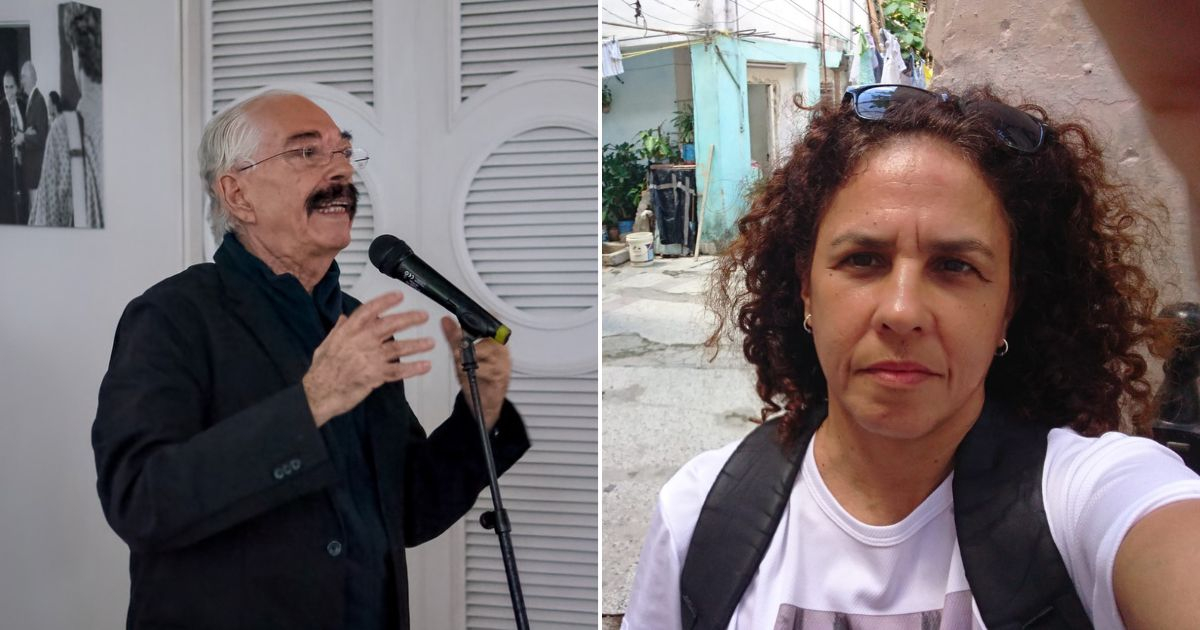

Cuban journalist Yania Suárez reported being expelled from the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba after participating in the screening and discussion of the documentary Landrián, by filmmaker Ernesto Daranas.

In a lengthy message posted on his Facebook profile, Suárez shared that he attended the event with several questions regarding the life of Nicolás Guillén Landrián, particularly concerning the lack of information about his relationship with the Cuban Committee for Human Rights (CCPDH), founded by Ricardo Bofill in the 1980s.

"I had my questions. I let others speak," he wrote, noting that Helmo Hernández, director of the Ludwig Foundation, intervened in the debate, describing the institution as a "place of worship for Guillén Landrián," "a pioneer in the dissemination of his work," and "a stronghold for 30 years against censorship."

However, when taking the floor, Suárez questioned the omission of key biographical aspects about the filmmaker's life and mentioned his possible connection to the Cuban Committee for Human Rights, as well as his participation in the First Exhibition of Dissident Art, held in front of Jalisco Park.

“At the moment I was recounting the story of Landrián’s participation to those present, Helmo Hernández interrupted me, visibly agitated, accusing me of being paid by someone to introduce an agenda into his space,” she reported.

"Almost hysterical, he refused to allow the kind of things I was doing. The sound engineer knocked down the microphones. Helmo stripped me of my right to speak."

Suárez responded to the interruption by calling Hernández "hypocrite" and pointed out that he acted just like the censors, despite the fact that Landrián had been a victim of censorship in Cuba. He ultimately stated that she was expelled from the venue.

Before leaving the room, she questioned the attitude of the foundation's director and accused him of engaging in "ad hominem" censorship, attacking her instead of responding with arguments.

"I have written this to document the mediocrity and falsehood of certain setups that, since the Revolution, pretend to be democratic," he expressed. Suárez concluded his denunciation by stating that the purpose of these events is to "sell foreign visitors the appearance of an accepted dissent within the Revolution," when in reality, censorship remains prevalent.

The journalist stated that she has an audio recording of the discussion, but for now, she has no intention of releasing it because "she doesn't like scandals."

The silencing of dissent in the history of Nicolás Guillén Landrián

In her research published in Hypermedia Magazine, Yania Suárez argues that the official recovery of Nicolás Guillén Landrián has been marked by strategic omissions regarding his biography, particularly concerning his possible connection to the Cuban Committee for Human Rights.

According to Suárez, the process of "rescuing" the filmmaker's figure has been directed by the ICAIC, the same institution that pursued and censored him during his lifetime, which has led to a selective reinterpretation of his history.

One of the most overlooked aspects, according to the author, is her possible involvement in the CCPDH, founded by Ricardo Bofill, a group that denounced human rights violations in Cuba and was heavily persecuted by the regime.

Suárez points out that documents such as the reports from America’s Watch and testimonies from exiles indicate that Landrián may have collaborated with this committee in his final years on the island.

In his article, Suárez also emphasizes that, in 1988, Landrián participated in the First Exhibition of Dissident Art, organized by members of the CCPDH in an apartment across from Jalisco Park.

During that event, not only were works by marginalized artists showcased, but microphones were also set up to denounce the victims of repression in Cuba.

Witnesses of that exhibition claim that Landrián was present and that his relationship with key figures of the dissidence, such as Adolfo Rivero Caro, suggests a deeper commitment to the opposition than the official narrative admits.

The reconstruction of his biography within Cuba has overlooked these aspects, choosing instead to frame him as a misunderstood artist and a victim of the extremism of certain officials, without addressing his direct challenge to power.

For Suárez, this omission is part of a well-defined strategy: to soften his history in order to make it compatible with the official version of the Revolution, which holds that only the mistakes of a few individuals—and not the system itself—are to blame for the abuses committed.

In this context, the journalist questions the authenticity of Landrián's "rescue," stating that his legacy will only be fully acknowledged when his dissent is recognized and the repression he endured for challenging the regime during his lifetime is acknowledged.

Censorship has been a constant in the history of the Cuban regime, systematically used to silence any voice that questions or challenges the official narrative.

The Cuban filmmaker Pavel Giroud reported on his social media that the 40th edition of the Jazz Plaza International Festival canceled the screening of his documentary “Manteca, mondongo y bacalao con pan” (2009), which was scheduled for Saturday, February 1, in the event's audiovisual lineup.

“Apparently, they regretted scheduling my documentary ‘Manteca, mondongo y bacalao con pan’ at the 23 and 12 cinema (Jazz Festival program),” the filmmaker emphasized on Facebook.

In January, the state channel Cubavisión announced through its official Facebook page the cancellation of the soap opera "Violetas de Agua", which was broadcast daily at 2:00 p.m.

According to the statement, the decision is due to "technical reasons," although the announcement has sparked speculation among viewers, leading to concerns that it might be another example of censorship.

However, the decision has sparked controversy on social media, following the revelation that the soap opera included the participation of the controversial influencer and opponent of the Cuban regime Alexander Otaola.

But the issue is not new. The Assembly of Cuban Filmmakers (ACC) concluded the year 2024 with a strong call to defend creative freedom and the denunciation of censorship affecting the world of audiovisuals.

In a statement released on its official Facebook profile, the organization highlighted the challenges faced by independent filmmakers and called for a change in the country's cultural policies.

Frequently Asked Questions about Censorship and Repression in Cuba

Why was Yania Suárez expelled from the Ludwig Foundation in Havana?

Yania Suárez was expelled from the Ludwig Foundation after questioning the omission of key biographical aspects about Nicolás Guillén Landrián during a debate about her documentary. When she pointed out the possible connection between the filmmaker and the Cuban Committee for Human Rights, the foundation's director, Helmo Hernández, interrupted her and accused her of having a hidden agenda, resulting in her expulsion from the event.

What aspects of Nicolás Guillén Landrián's biography are omitted in Cuba?

In Cuba, important aspects of Nicolás Guillén Landrián's biography are omitted, such as his possible connection to the Cuban Committee for Human Rights and his participation in the First Exhibition of Dissident Art. These details are ignored to soften his story and make it compatible with the official narrative of the Revolution, which blames individual mistakes rather than the system itself.

How does censorship manifest in cultural events in Cuba?

Censorship at cultural events in Cuba is expressed through the exclusion of works and creators that criticize the regime, the manipulation of history in exhibitions, and the repression of dissenting voices. Recent examples include the cancellation of critical documentaries at festivals and the expulsion of artists and journalists from cultural events for questioning the official narrative.

What is the current situation of freedom of expression in Cuba?

Freedom of expression in Cuba is severely restricted. The regime systematically represses independent journalists and artists through arbitrary detentions, censorship of works, and threats. This repression has intensified with new laws that criminalize the receipt of foreign funding and further limit freedom of expression.

Filed under: