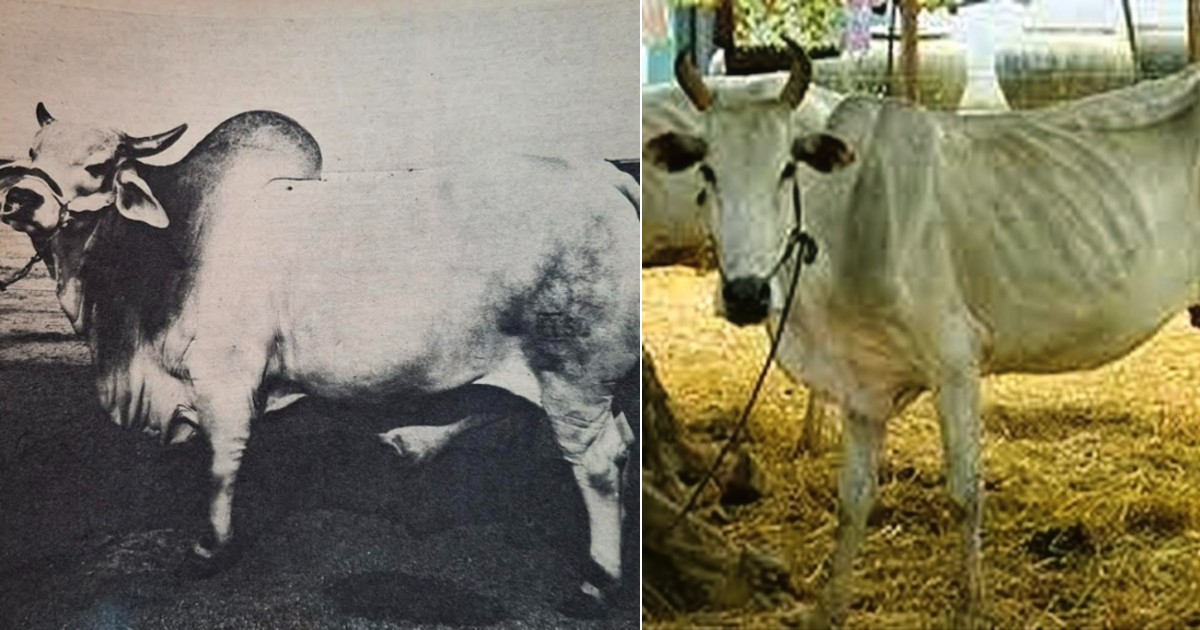

In 1956, the population of Cuba was 6 million 676 thousand people. The zebu was the predominant breed in Cuban pastures, with 6 million heads of cattle, which amounted to approximately 0.90 cattle per inhabitant.

This does not include the smaller livestock, which totaled 4 million 280 thousand animals, including 500 thousand equines, 3 million 400 thousand swine, and 200 thousand sheep, among others.

According to the FAO in 1953, Cuba held a good position in cattle per capita among the 36 most important countries. Additionally, it ranked just below Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil, which were then the main exporters of meat in Latin America. Therefore, holding the fourth place was an honor for a country whose fundamental economic sector was the sugar industry, not livestock farming.

According to the publication by the National Association of Cattle Ranchers of Cuba in 1956, 30 sectors of the national economy benefited directly or indirectly from cattle and its products.

With an investment of 1.451 billion dollars, this sector generated nearly 342,000 jobs and more than 105 million dollars in salaries and wages.

On the island, there were, to mention a few of these sectors, 718 dairy farms (with 350,000 dairy cows), 27 jerky factories, 502 ice cream shops, 153 saddle-making shops, 4 powdered milk factories, 23 cheese factories, 18 butter factories, 10 ice cream factories, and 2,962 fur shops, among others.

Not even wars were able to put an end to Cuban livestock farming.

In 1868, during the Ten Years' War, the pastures were devastated and it was necessary to rebuild them. The coffee plantations, sugar mills, and large stocks of livestock were used to raise money or feed the troops.

By 1894, on the eve of the Grito de Baire, the pastures had 2 million 485 thousand cattle. However, in 1899, at the end of the war and with the American occupation of the island, a census recorded only 376 thousand cattle. With the livestock wealth completely devastated and the need to feed workers and support agricultural activities, tariff facilities were implemented to rebuild cattle farming on the island. Cattle were introduced from Florida, Texas, Tampico, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela. Ranchers dedicated themselves to restoring this wealth, and by 1910 there was already a stock of over 3 million cattle.

World War I in 1914 was another tough test for Cuban livestock. The import of food was drastically reduced, and the enormous demand for sugar and tobacco forced the use of oxen for the cultivation and transportation of cane, essential for the large harvests and the creation of sugar mills. With the Tariff Reform of 1927, derivative industries were established that allowed for the development and growth of national products, eliminating the need for imports.

In 1945, during World War II, the highest demand for livestock for supply was reported in all of history. By 1952, in a census that lasted 100 days and during which not all farms could be visited, 5 million 300 thousand cattle were recorded.

From Abundance to Scarcity: 65 Years of Livestock Decline in Cuba

Since 1959, the cattle population has not stopped decreasing. The government initially blamed acts of sabotage and internal opposition.

In 1990, despite the island's population being 11 million inhabitants, the cattle herd was reduced to only 4.8 million heads, and only about 20% of these belonged to private producers (cooperatives).

The poor management of Cuban livestock that contributed to the crisis can be attributed to several structural factors and political decisions that generated a high external dependency and a poorly adaptable system. The main problems were:

Dependency on imported inputs: Cuban livestock relied heavily on external inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides, wires, agricultural machinery, fuels, and raw materials for the preparation of concentrates. When the economic crisis occurred and imports were reduced, the system could not sustain itself.

Intensive and costly production system: The Cuban model was based on an intensive system that required a large infrastructure, including tractors, trucks, and machinery to distribute food and manage livestock activities. This generated high costs and a critical vulnerability to any interruption in the supply of resources.

Inability to adapt to adverse weather conditions: The lack of responsiveness to droughts and climate changes was a key factor. The grasses and forages, essential for livestock feeding, deteriorated rapidly due to a lack of fertilizers and water. Furthermore, there was no effective strategy to manage these contingencies sustainably.

Failure in genetic management and reproduction: The implementation of artificial insemination, although initially successful, became unsustainable due to the lack of necessary supplies such as liquid nitrogen and equipment. This forced a return to less efficient methods, such as direct breeding, negatively affecting the productivity and genetic quality of the herds.

Poor land use planning and pasture management: The lack of fertilizers and pesticides led to the degradation and infestation of pastures with weeds, such as aroma and marabú, affecting more than a million hectares of agricultural land. Salinity also played a role in the loss of land quality, which was not properly managed.

Dependence on the sugar industry: The Cuban livestock system was closely linked to the sugar industry, as many of its by-products were essential for feeding the cattle. The crisis also affected this industry, reducing the production of sugar and honey, which negatively impacted livestock farming.

In summary, the crisis in Cuban livestock resulted from a combination of external dependency, lack of adaptability in the production system, and mismanagement of resources and land, which led to the collapse of the sector when faced with the economic crisis.

Current official censuses do not accurately record deaths, thefts, and illegal slaughtering of cattle, making them unreliable. In 2023, more cows died in Havana than were born, and authorities claim that one of the main causes of the deaths was malnutrition, primarily in calves.

It is estimated that the country barely reaches a figure of 3 million 645 thousand head of cattle for a population of nearly 10 million inhabitants.

What do you think?

COMMENTFiled under: