Related videos:

The President of the United States, Donald Trump, has once again placed Venezuela at the center of international controversy by publicly demanding that the government of Nicolás Maduro return “all the oil, land, and assets they stole from us.”

His message, recently shared on his social network Truth, has had a global impact and provoked an angry response from the Chavista regime, which described it as "an imperialist and absurd threat."

The White House later confirmed that the Trump administration ordered a total blockade of sanctioned oil tankers transporting Venezuelan crude, a measure that Washington justifies as part of its strategy to prevent the Maduro regime from financing itself through oil.

The State Department added that the president's statement refers to a series of U.S. assets and investments expropriated by Venezuela during the administrations of Hugo Chávez and Maduro himself.

The expropriations that defined two decades

Although there is no single document that consolidates all the nationalized American assets, international arbitration records and reports from the Venezuelan-American Chamber of Commerce show a clear pattern: Venezuela expropriated or confiscated more than a dozen American companies since 2007, when Chávez launched his plan for “reverting energy sovereignty.”

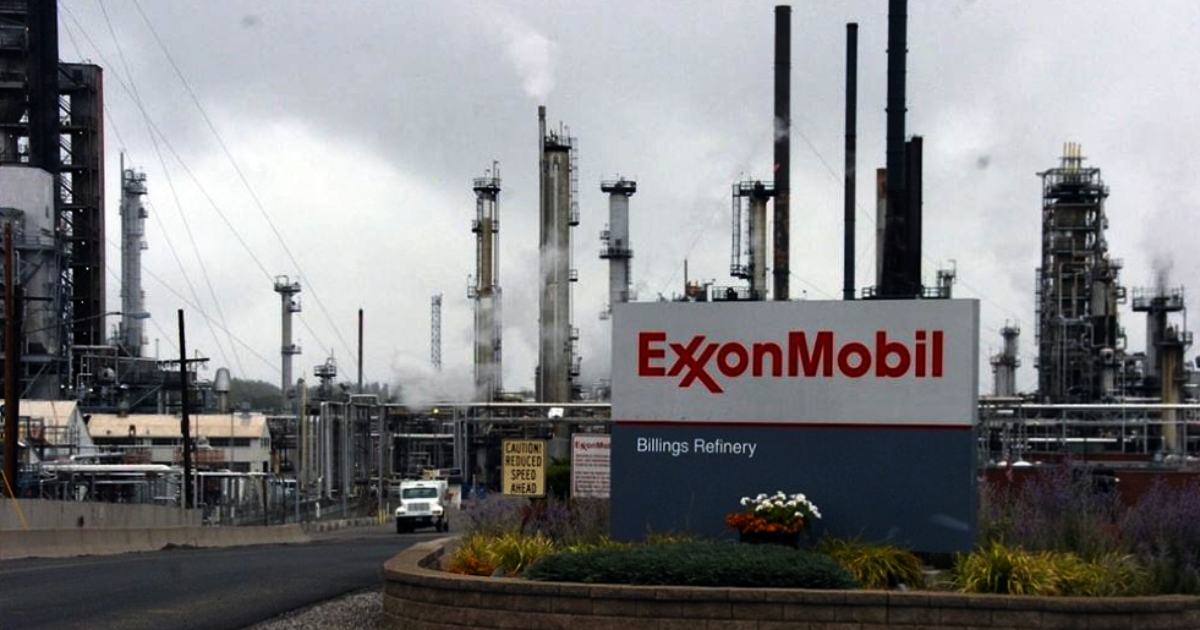

ExxonMobil (2007)

That year, the government required foreign oil companies to transfer the majority of their shares in projects within the Orinoco Oil Belt to PDVSA. ExxonMobil rejected the agreement, and its assets were expropriated.

The company sued Venezuela before the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), which in 2014 awarded it a compensation of 1.4 billion dollars. Caracas paid only a portion and remains under the scrutiny of international courts.

ConocoPhillips (2007)

The most costly case for Venezuela. Its stakes in the Petrozuata, Hamaca, and Corocoro projects were nationalized.

In 2019, an ICSID tribunal ordered the payment of $8.7 billion to ConocoPhillips for unlawful expropriation, the largest ruling of its kind against the country.

Owens-Illinois (2010)

The American glass packaging manufacturer was nationalized by presidential decree. In 2015, the ICSID ruled in its favor, determining that Venezuela had violated the bilateral investment treaty with the U.S.

Clorox (2014)

The company abruptly closed due to economic insolvency; days later, the government took over its facilities and ordered its operation under state control.

General Motors (2017)

The regime confiscated an assembly plant in Valencia and the company's assets, citing labor disputes. GM referred to the event as an "illegal expropriation" and ceased its operations in the country.

Kellogg’s (2018)

The multinational food company left the country due to hyperinflation and price controls. Maduro announced that the plant would continue operating "under workers' management," with no known compensation.

Chevron (2025)

The last major American oil company that maintained joint operations with PDVSA under special licenses from the U.S. Treasury.

In 2025, the licenses were temporarily revoked, and the assets were placed under Venezuelan administration, although there is still no formal expropriation process in place.

Oil service companies (Halliburton, Schlumberger, Baker Hughes, and Weatherford)

Between 2018 and 2025, these companies drastically reduced their presence or suspended operations due to sanctions and unpaid debts. Although there were no declared confiscations, their equipment and machinery remained detained in Venezuelan territory.

Beyond oil

The expropriations were not limited to the energy sector. Between 2009 and 2015, the Venezuelan government took control of more than 5,000 national and foreign companies, according to data from the Venezuelan Confederation of Industrialists (Conindustria).

Of them, at least 20 had total or partial U.S. capital, including manufacturing, food, service, and telecommunications firms.

The response from Caracas

The Venezuelan Minister of Communication, Freddy Ñáñez, responded to Trump's statements, labeling them as "political blackmail" and asserted that "Venezuela will not return a single asset to the monopolies of imperialism."

However, the Venezuelan opposition believes that these expropriations were part of the national economic collapse, as they destroyed foreign investment and legal guarantees.

A claim with legal and political roots

Experts in international law agree that Trump's phrase—"return the stolen assets"—does not imply a claim to territorial ownership, but rather a demand for overdue compensations recognized by international arbitration awards.

The United States, as a state, does not own those assets, but represents the interests of the affected companies, which have won the majority of the international lawsuits.

Meanwhile, the verbal confrontation between Washington and Caracas reignites geopolitical tension in the region at a time of maximum economic pressure on the Chavista regime.

For Venezuela, the claims represent the cost of its expropriation model; for Trump, it is just another political argument in his crusade against the regimes allied with Cuba, Russia, and Iran.

Filed under: