The Cuban regime has formalized a legal norm that regulates assistance to individuals with "wandering behavior," a state euphemism for those who beg, live on the streets, or lack family support.

This refers to Agreement 10056/2025 from the Council of Ministers published in the Official Gazette, which has been in effect since April 28. It defines this phenomenon as "a multicausal human behavior disorder" that involves "instability and insecurity at home, lack of self-care and economic autonomy, absence of family support or protection, as well as a favorable life project."

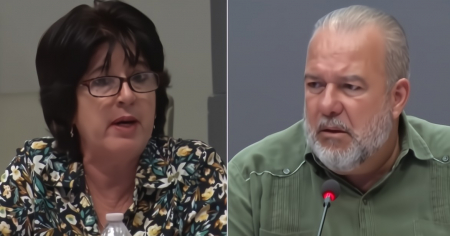

The regulation states “the action towards those who, without having an associated intellectual or mental disability, refuse prophylactic work,” as affirmed by Belkis Delgado Cáceres, director of Prevention, Assistance, and Social Work at the Ministry of Labor and Social Security (MTSS), to the official newspaper Granma.

The Cuban regime's approach avoids openly discussing extreme poverty or destitution, using euphemisms that dilute the seriousness of the problem and its structural origins.

How is care organized?

Despite being a complex social phenomenon, the control of the "street dwellers" is left in the hands of local authorities, as stipulated by the legal norm recently approved by the government.

The provincial governor is responsible for coordinating the system, while the municipal mayor will be the one to establish and lead multidisciplinary teams in order to classify cases and define strategies for care, reintegration, and monitoring.

The groups will be composed of social workers, Public Health personnel, and the Police. When dealing with minors, officials from the Education sector, officers from the Ministry of the Interior's juvenile division, and, if the nature of the matter requires it, representatives from the Attorney General's Office and the People's Tribunal in the municipality will also be included.

These groups will be responsible for "the assessment, classification, and design of sustainable solution strategies for the care of individuals exhibiting wandering behavior, ensuring their reintegration into their family unit, and monitoring and following up on... those individuals who roam in areas that are not their place of origin and, therefore, it is necessary to return them to their place of residence," Delgado stated.

The approach is clear: containment and a "return" to their territories of origin, without guarantees of real reintegration or respect for the wishes of those involved.

Protection Centers: temporary confinement, without structural solutions

According to the official from MTSS, the Social Protection Centers are the institution for comprehensive care of individuals who "due to various economic and social reasons, are without a permanent home, in a state of abandonment, or lack relatives able to provide assistance, with a voluntary short-term stay of up to 90 days."

As of now, there are nine institutions of this type in Pinar del Río, Havana, Matanzas, Villa Clara, Ciego de Ávila, Camagüey, Holguín, Granma, and Santiago de Cuba, and the establishment will be assessed in the provinces that do not yet have them.

Delgado warned that “it is not about keeping a person indefinitely in these centers, but rather seeking facilities that allow them to reintegrate into the environment to which they belong.” In the case of elderly individuals, he stated, “they can be placed in nursing homes, if necessary, due to a lack of support and assistance from family.”

For individuals under 60 years old, he mentioned the promotion of initiatives for job and social integration, contributing to the rehabilitation of potential drug or alcohol addictions, as well as comprehensive care and assessment by health personnel.

Furthermore, the governors are responsible for "the allocation of temporary facilities, a shelter, the provision of housing, and the approval of subsidies for the repair and construction of housing for these wandering individuals," according to the regulations.

Although the official discourse mentions reintegration, medical care, and addiction treatment, no statistics are provided on how many people have actually benefited, been reintegrated, or whether these facilities offer minimum living conditions.

Protocol for identifying, classifying, and reporting

The Cuban government also formalized the protocol for identifying individuals with wandering behavior "or those prone due to the level of family neglect they exhibit" within at-risk communities, groups, and families, managed by social workers, as well as doctors and nurses from family health clinics.

If minors are detected in this situation, "it should be urgently communicated to the relevant department of the Ministry of Education or the Ministry of Public Health, so they can ensure immediate placement in one of the social assistance centers dedicated to these purposes; provided that there is no family member or emotionally close person who can take charge; and it should be reported to the Prosecutor's Office while the necessary investigations are carried out or another protective measure is adopted to determine if there is a breach of parental responsibility," Delgado stated.

In practice, this is a policy of surveillance and social control disguised as assistance. There are no independent supervision mechanisms, nor is voluntary participation of those affected guaranteed. Rights are not mentioned, only duties and discipline.

Hiding the poor without eradicating poverty

The measure does not clearly address how to reverse begging but rather how to manage its visibility. As a user commented on the official portal Cubadebate: “One thing is to eradicate begging, and another is to eradicate beggars.”

It also does not address the structural causes of the phenomenon, which are centered on the collapse of the economic model, family disintegration, demographic aging, and massive emigration. The state does not acknowledge its responsibility in this crisis and opts for reactive measures to conceal its symptoms.

The institutionalization of control over the poorest, labeled as "vagrancy," is nothing more than another authoritarian patch to disguise a social fracture that can no longer be hidden.

The Cuban regime attributes the increase in the number of homeless individuals to family neglect and the tightening of the United States embargo.

A recent report by the official newspaper Girón has revealed one of the most painful realities of present-day Cuba: the extreme precariousness in which thousands of retirees live who, after decades of work, are forced to survive on the streets.

The Cuban leader Miguel Díaz-Canel has had to acknowledge the existence of concerning social issues such as child labor, begging, informal employment, and the harassment of tourists, something that the state-run media highlighted as a reality often silenced in Cuba.

Since mid-2024, the government began to strengthen its institutional narrative regarding the increasing presence of homeless individuals on the streets of the country.

In June, an update to state policy aimed at addressing the issue of homeless individuals was announced, with a focus on their forced relocation to social protection centers. Previously, authorities reported that the number of homeless people on the island had tripled.

Socially, there is a concern about the growing inequality and impoverishment that the country is experiencing, a phenomenon highlighted by the British newspaper The Times, which months ago described the reality of Cuba as “a country in ruins, where people are starving.”

As of 2023, Cuba was considered the poorest country in Latin America, according to DatoWorld, a well-known international electoral observatory that assesses parameters such as per capita income, access to health services, social security, nutrition, and housing conditions.

The country has a poverty rate of 72%, placing it at the forefront of the Latin American region.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Situation of the "Street Dwellers" in Cuba

What is Agreement 10056/2025 and how does it affect the "deambulantes" in Cuba?

The Agreement 10056/2025 of the Council of Ministers of Cuba is a legal norm that regulates the treatment of individuals with "wandering behavior." This agreement aims to control the visibility of begging without addressing its structural causes, such as extreme poverty and the collapse of the Cuban economic model. The measure focuses on containment and the return of these individuals to their areas of origin, without ensuring real reintegration or respecting the wishes of those involved.

What role do Social Protection Centers play in assisting "street dwellers"?

The Social Protection Centers in Cuba are institutions dedicated to the comprehensive care of individuals without a fixed residence or in a state of abandonment. They allow for voluntary coexistence for a short term of up to 90 days, but do not provide long-term structural solutions. Although there is talk of reintegration and medical care, there are no clear figures on how many individuals have truly benefited from these measures.

How is the issue of begging being managed in Cuba?

The Cuban regime's approach to begging is focused more on managing its visibility than on eradicating its causes. Official policies tend to blame family neglect and external factors, such as the U.S. embargo, without addressing the structural roots of the problem. This is reflected in reactive measures and in a governmental discourse that downplays the State's responsibility in the social crisis.

What criticisms does the Cuban government's approach to "vagrants" face?

The Cuban government's approach to "vagrants" has been criticized for its lack of attention to the structural causes of poverty and for using euphemisms that dilute the seriousness of the issue. The regime opts for measures of social control and containment, rather than providing effective solutions. These policies have been viewed as an attempt to hide poverty without eradicating it, reflecting a failure to address the underlying economic and social crisis.

Filed under: