Related videos:

When Arleen Rodríguez confidently stated that “José Martí did not know electric light and was a genius,” she not only displayed an unforgivable ignorance: she insulted Martí himself and the intelligence of Cubans. In the city where he spent his last years, New York, the electric light of Thomas Alva Edison was already thriving, which the Apostle contemplated, studied, and celebrated as one of the great wonders of modernity.

Arleen's phrase and the moral blackout

“Is the blackout terrible? Well, José Martí didn’t know electric light and he was a genius,” Rodríguez said, attempting to downplay the suffering caused by the blackouts currently afflicting the Island. The underlying message is clear: if the Apostle could create in the darkness of the 19th century, the Cuban citizen of the 21st century should not complain about being without power for hours or days. This comparison, made during an interview program with Rafael Correa, comes amid prolonged power outages, spoiled food, and a weary nation, and aims to turn resignation into patriotic virtue. Correa himself, uncomfortable, counters with a phrase that disarms it: “But Arleen, we are in the 21st century,” reminding her that progress is not a luxury, but a basic right of any contemporary society.

The problem is not only factual but also ethical. The journalist does not simply make a mistake about a historical fact; she distorts the figure of Martí and uses it as an ideological shield to justify the energy failure of a regime that has been unable to provide a stable service. Turning the Apostle into a patron of blackouts, a symbol of stoic acceptance of hardship, is a discursive operation that degrades his thought and institutionalizes backwardness as the norm.

Who, in 2026, invokes Martí to justify 40-hour power outages places themselves, without shame, on the side of darkness against the light that Martí admired and defended.

Martí in New York: the witness of light

José Martí lived in New York, coming and going, from 1880 to 1895, precisely when the city was transforming into a showcase of electrical modernity. In 1882, Edison launched one of the first electric street lighting systems in Manhattan, and the metropolis began to glow with incandescent lamps that extended urban life beyond sunset. Martí was not a passive observer: he walked those streets, witnessed those lights being turned on, attended industrial exhibitions, and read and wrote about the technological revolution that was changing everyday life.

In his columns for magazines like La América, the Cuban repeatedly focused on advancements in science, with particular attention to electricity. He was not just a mere impressionable enthusiast; he studied the functioning of machines, described their applications, and translated technical language into terms easily understood by the general public without losing accuracy. For him, electricity was one of the key elements of the new industrial era, capable of transforming production, transport, communication, and even the way humans perceived the night. The Havana native exiled in New York was, in this regard, a privileged chronicler of the moment when the world began to light up.

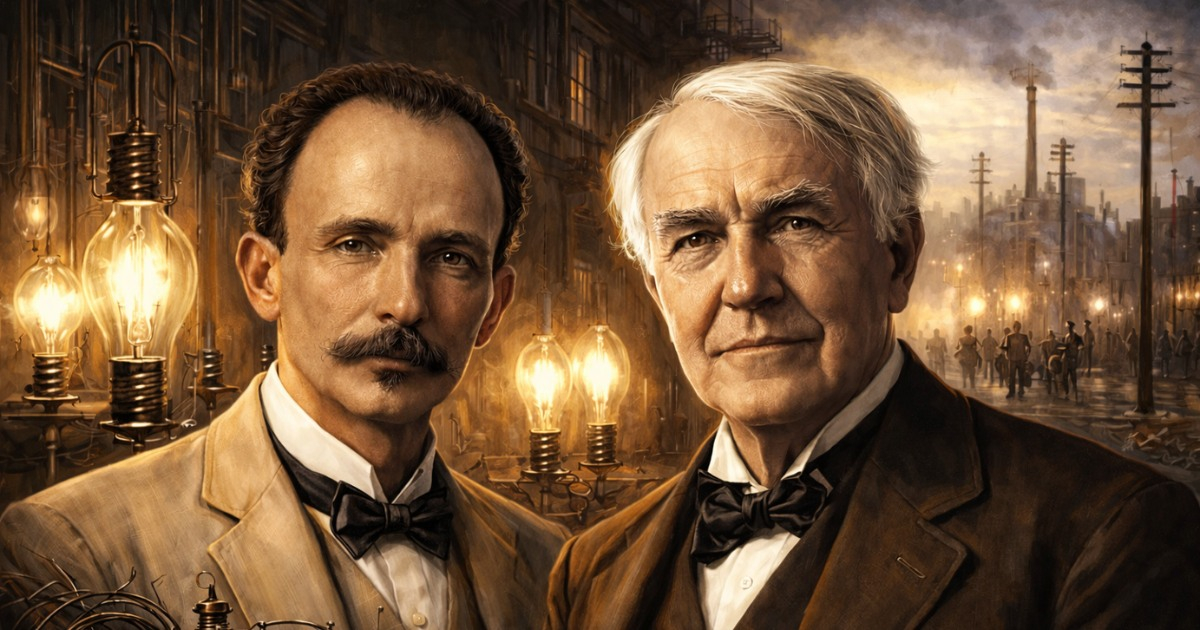

Martí and Edison: Fascination with the “Beautiful Electric Light”

If there is a name associated with that luminous revolution, it is Thomas Alva Edison, and Martí was well aware of it. In texts like “Edison Light,” he expressed his admiration for the inventive capacity of the American and the social impact of his innovations. Far from being unfamiliar with electricity, Martí was an enthusiastic promoter of incandescent lamps, generating stations, and distribution systems that were beginning to gain traction in theaters, banks, workshops, and streets. He writes that Edison’s electric light “thrives and conquers cities,” emphasizing not only the technical novelty but also the speed at which technology was asserting itself in urban life.

His perspective on Edison’s machines blends precision with poetry. He describes the installations as “slender and simple, yet heavy and graceful, like a giant's toy,” an image that reveals both knowledge of the mechanism and an aesthetic sensitivity towards modern engineering. He speaks not as someone who has heard secondhand, but as someone who has seen, questioned, and observed the intricacies of the gears. For Martí, Edison embodies the type of scientist who uses his talent to change the world, and electricity is the tool that breaks the barrier of darkness and expands human capacity to work, study, and enjoy.

In other accounts, Martí refers to electricity as the central force of the new era, applied to mining, agriculture, medicine, navigation, and meteorology. He even speaks of electricity as a kind of sap of the modern world, a metaphor that resonates strongly today in a country where power outages paralyze hospitals, industries, and homes. This vision is incompatible with the attempt to portray him as a writer resigned to candles and oil lamps, disconnected from the technological wonder that surrounded him.

The Electric Idea: Science, Dignity, and Future

The relationship of Martí with science was not merely decorative. In his texts from La América, a philosophy of technology emerges that views it as a tool for emancipation rather than oppression. For him, scientific progress should serve "the poor of the earth," elevate their standard of living, and grant them access to education, knowledge, and material well-being. Electricity, in that program, represents the possibility of illuminating schools, hospitals, workshops, and fields; extending the useful hours of the day and making existence safer and more productive.

That "electric idea" permeates his thinking: light is not only a physical phenomenon, it is a metaphor for moral clarity, political transparency, and openness to the future. That today his name is invoked to normalize darkness is, therefore, doubly offensive. It is not only historically false to claim that Martí did not know electric light; it is that the Apostle is used to preach technological stagnation, resignation in the face of precariousness, and the praise of backwardness.

While Martí celebrated every technical advancement that brought America closer to the development levels of industrial powers, the contemporary official discourse seems intent on turning deficiency into virtue and labeling what is often mere incompetence as "resistance." In Martí's thinking, science and technology are allies of freedom; in Arleen's narrative, it is hinted that they are not so necessary, that one can do without them if there is "genius" and sacrifice. It is a complete inversion of the original meaning.

Arleen's ignorance and the betrayal of Martí

Arleen Rodríguez's statement is not an isolated slip, but rather a symptom of an official culture that manipulates history to uphold an indefensible present. Presenting Martí as a genius without electricity serves to deliver a political message: if the greatest of Cubans could live without current, then today's citizen has no right to demand it. Factual ignorance—denying that the Apostle knew, described, and celebrated electricity—thus becomes a tool of social control.

But this narrative comes at a high cost: it distorts Martí's image to the point of making it unrecognizable. The man who was moved by Edison’s "beautiful electric light" and saw science as a pathway to the dignity of the poor cannot be used as a pretext to keep an entire country in both physical and symbolic darkness. By reducing him to a saint of suffering, the official discourse betrays his modernizing legacy and his faith in progress.

If there's one thing that an honest reading of his texts makes clear, it's that Martí envisioned a bright future for Cuba, in the most literal and profound sense of the term. He wanted schools filled with light, workshops equipped with machines, vibrant cities at night, farmers with access to technology, entire communities connected to the currents of universal science. Whoever invokes his name in 2026 to justify 40-hour power outages not only errs in the facts: they shamelessly align themselves with darkness against the light that Martí admired and defended.

Filed under:

Opinion article: Las declaraciones y opiniones expresadas en este artículo son de exclusiva responsabilidad de su autor y no representan necesariamente el punto de vista de CiberCuba.