Related videos:

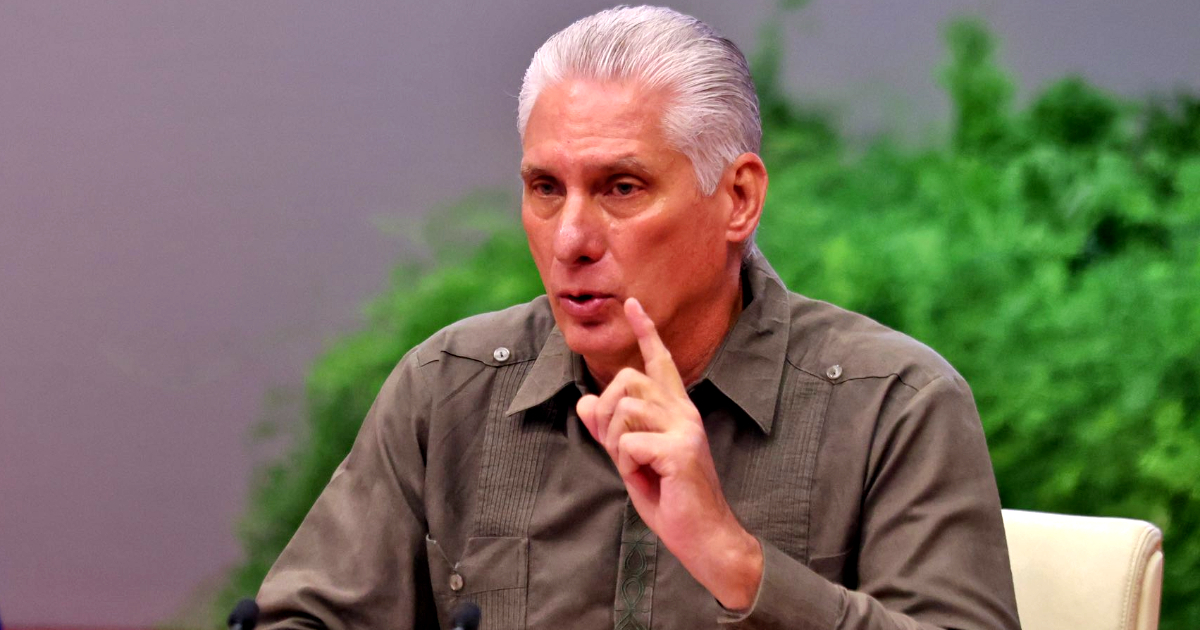

The speech by Miguel Díaz-Canel at the XI Plenary of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) was presented by the official press as an exercise in self-criticism and “revolutionary updating.”

However, what the designated leader actually offered was a systematic reiteration of the old empty formulas of Castroism: resistance, blockade, unity, and struggle. At first glance, it seemed like a working meeting; in essence, it was a political survival act.

From the outset, Díaz-Canel acknowledged the magnitude of the crisis: a Gross Domestic Product in decline of over 4%, rampant inflation, prolonged blackouts, food shortages, and a general deterioration of daily life.

But despite that precise overview, the president opted for a familiar explanation: “six decades of external economic harassment.” Once again, the blockade was the discursive refuge for all ills, the scapegoat that allows for evading internal responsibility and accountability to the population.

The contrast between the diagnosis and the causes provided by the authorities reveals a constant: "continuity" no longer speaks to the country, it speaks to itself.

Díaz-Canel repeats the mantras of classical Castroism—"resistance," "unity," "popular participation"—but without the epic qualities or faith of the founding years. The tone is no longer heroic but bureaucratic: a blend of slogans from Ñico López with procedural manuals from GAESA and Counterintelligence.

Throughout the speech, Raúl Castro's appointee returned to the same rhetorical axis that has characterized his interventions: an emotional appeal to revolutionary morality combined with administrative promises.

"Correct distortions and reinvigorate the economy," he said, without explaining how to do so in a system that punishes private initiative, centralizes decision-making, and maintains a state monopoly in nearly all sectors.

The contradiction between words and reality was mainly expressed in language. When Díaz-Canel spoke of “revolutionizing the Revolution,” he was, in fact, announcing the continuation of an unchanging model. The promise of change has turned into an empty slogan, repeated at every congress, assembly, and presidential speech for at least the past twenty years.

Even more revealing was his insistence on "unity" as a strength. In a country with only one legal party and no political pluralism, this appeal to unity does not signify consensus but rather obedience. What the first secretary of the PCC described as "strong discussion" or "critical debate" is, in practice, a closed conversation where all conclusions have already been decided before it even begins.

The XI Plenary was meant to be an opportunity for evaluation and strategic reassessment for the communists, but it ended up being an ideological reaffirmation of impotence and incompetence. The leaders acknowledged the difficulties but did not question the foundations of the system that generates them. Thus, the discourse turned into a circular exercise: diagnosing the same problems, repeating the same promises, and once again blaming the same enemy.

Meanwhile, Cuban society is moving in another direction. People are emotionally disconnecting from the official narrative, seeking informal alternatives to survive, and emigrating as a form of silent protest. The "revolution" that once promised dignity has turned into a mechanism that manages scarcity and demands gratitude for it.

The contrast between triumphalist rhetoric and everyday life undermines the legitimacy of power more than any lament about a "leaky blockade." When Díaz-Canel calls for trust and patience, many Cubans only hear repetition and inertia. The discourse has lost the fervor of the political charisma of the chief dictator and has turned into a litany of justifications from the timid heir to the position.

Ultimately, what Díaz-Canel said was the same as always: that the country can continue as it is, as long as the people keep believing. But faith, unlike control, cannot be imposed by decree.

Filed under: