Related videos:

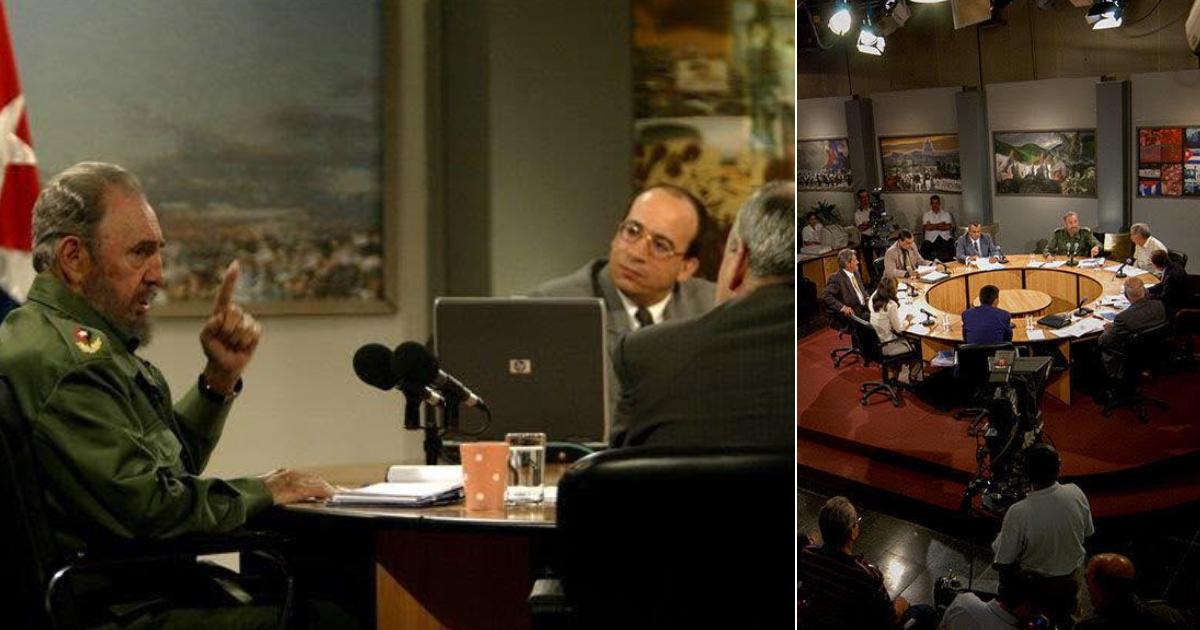

The Cuban ruler Miguel Díaz-Canel celebrated the 26th anniversary of the television program Mesa Redonda, conceived by Fidel Castro, with a message on Facebook that sparked mixed reactions, although the majority expressed discontent among users.

"Twenty-six years ago, a communication space conceived by Fidel was born in the heat of the struggle to rescue the Cuban child Elián González, kidnapped in the United States," wrote the leader in his Facebook post, accompanied by several images of the deceased leader. In the text, he emphasized that the first broadcast of the program, titled What time can a child's mind be changed?, marked “an era that, through intelligence, talent, and commitment, defined the Battle of Ideas.”

The message, in which he congratulated the creators for "continuing to support the essential struggles of Cuba," quickly triggered an avalanche of critical comments. Many users felt that the post was a reflection of the government's disconnection from the everyday reality of the country.

"How great that you have electricity so you won't miss the Mesa Redonda; I lost track of how long it has been since I could watch TV or sleep with a fan," commented one person, referring to the blackouts plaguing the island. Another internet user sarcastically remarked: "They learn how to endure hunger, epidemics, the lack of healthcare, electricity, water, and freedom."

Some also compared the space to a symbol of state indoctrination: “The reticent table, where what is said is not what is truly thought, only what the bosses want to hear.” Another user wrote: “The space where the people are lied to and those who think differently are mocked.”

Some mocked the current context of the country: "It can be round, square, or triangular; without power, who sees it?" Others added: "Given the going rate for ideas, to accompany today's plain rice," or "The country is advancing, yes... in filth, hunger, and misery."

The references to the case of Elián González also sparked controversy. One user commented: “That boy was not kidnapped; his mother took him out of the country and died trying to save him,” while another replied: “The true kidnapper of the truth is you.” In another message, it read: “Kidnapped by the United States, you say; when the United States saved his life and the regime used him as a political trophy.” Although some comments expressed support for the leader—congratulating the program's team and defending its role as “a space of dignity and resistance”—among the harsher responses were phrases such as: “Stop romanticizing these communists who have destroyed the country” and “Thanks to you, Cubans have only learned to endure misery.”

Reactions reflect a recurring pattern in the publications of the Cuban leader. Just a day before, during the XI Plenary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, he had passionately stated that “no one is going to surrender here”, in a speech that also ignited social media with messages of discontent over misery, power outages, and lack of freedoms.

The contrast between the triumphant messages from those in power and the citizens' criticisms highlights the widening gap between the official narrative and the daily lives of Cubans, characterized by precariousness, information censorship, and an unprecedented crisis.

The previous anniversary of the program was also marked by propaganda. Last December, on the 25th anniversary of the first broadcast, Elián González, who has become a deputy of the regime, cried while recalling Fidel Castro and stated that the Mesa Redonda “made him a person.” In his speech, he claimed, “I truly became a person because of you,” expressing gratitude to the program for shaping his character and considering it “the cornerstone” of his current life. He also lamented having “known and lost too young” the dictator.

Filed under: