Related videos:

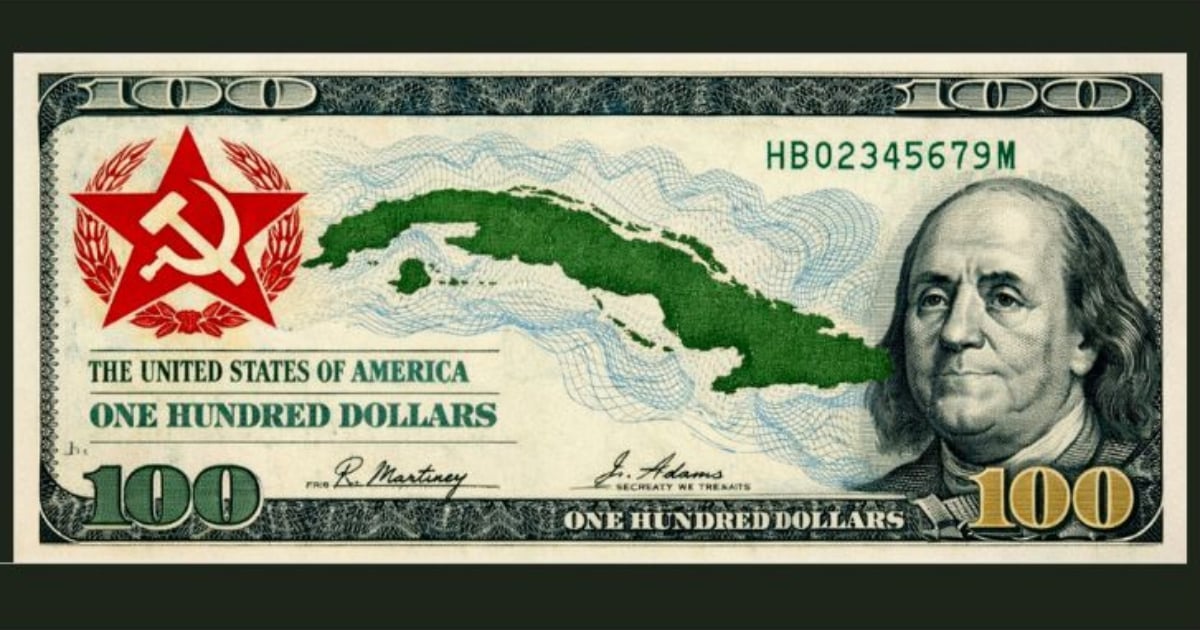

The new exchange system announced by the Central Bank of Cuba (BCC) is presented by the regime as a structural reform to “organize the foreign exchange market” and “strengthen the Cuban peso.”

In practice, however, it is a political maneuver to support businesses in power and to simulate an openness that does not exist.

Three official exchange rates, a controlled "floating" market, and the promise of stability create a narrative that sounds like modernization, but conceals the usual: centralism, inequality, and deception.

Three cups, one single direction: Control

As of December 18, 2025, Cuba operates with three official exchange rates:

- 1 CUP = 24 USD, reserved for the State for "essential" imports: energy, transportation, medicines, and food.

- 1 CUP = 120 USD, for companies with external income and some exporters.

- A daily floating rate, supposedly determined by supply and demand, applicable to individuals and non-state management forms.

At first glance, it appears to be a technical attempt to "segment" the economy. However, as the economist Mauricio de Miranda Parrondo warned, what the government is truly doing is consolidating an unequal and fictitious system, where the rules are adjusted to serve the interests of the military-business power.

"What is the point of maintaining two fixed rates and one floating rate? It's absurd," wrote the academic. "The only thing achieved is to favor state imports and penalize the productive sectors that generate real wealth."

The favor to GAESA

The analysis by De Miranda highlights a critical point: the main beneficiary of this system will be GAESA, the military conglomerate that controls tourism, foreign trade, and a significant portion of the country's finances.

With a rate of 1x24, GAESA companies —which import consumer goods and operate in dollars— will be able to access cheap foreign currency for their operations, while the rest of the economy will have to do so at higher prices or directly in the informal market.

"They want to provide special conditions to certain segments (GAESA among them) to operate with an unsustainable rate, while the rest of the players bear the burden of the crisis,” denounced the economist.

The result is a deeply unjust dual market: a privileged exchange rate for state-owned companies and a more expensive and restrictive one for the private sector, which remains excluded from legal access to foreign currency.

A "floating" rate that doesn't float

The BCC promises that the new "floating" rate will be updated daily and will reflect the real conditions of the market. However, there is no free currency market in Cuba: the state controls all banks, CADECAs, and exchange points.

In this context, talking about "floating" is an administrative fiction. "The minister of the BCC intends to tell the market at what rate it should operate. That’s not how the economy works," De Miranda explained. "A floating rate only exists if there is real supply and demand; in Cuba, what exists is an imposed rate."

The economist recalled that in normal countries, exchange rates vary slightly between banks or money exchange desks, and the central bank then publishes a representative market rate.

In Cuba, it happens the other way around: first, the political figure is imposed, and then the market is expected to adapt to it.

The economic lie

The Cuban regime justifies this system with a paternalistic discourse: “Avoid sudden devaluations to protect the population.”

But the reality is that Cubans will not be able to operate under either of the two fixed rates and will only have access to the "floating" segment, where the value of the dollar will depend on the limited flow of official currencies.

Meanwhile, domestic prices will continue to be referenced to the informal market, where the dollar reaches 440 CUP.

The gap between official fiction and the reality of people's wallets will grow, along with distrust in the Cuban peso and the impoverishment of the majority.

The measure, instead of correcting distortions, institutionalizes them. The state intends to compete with the black market, but without offering real rates or sufficient currency.

What is theoretically intended to "stabilize" will, in practice, only fuel informality, corruption, and the discrediting of the financial system.

Conclusion: A market for power, not for the people

Behind the technical language and charts of the Central Bank lies an old authoritarian recipe: controlling the flow of dollars to sustain the State, not to revive the economy.

The people, small business owners, and workers will remain excluded from real access to foreign currency and condemned to survive in a segmented economy, with unreal prices and worthless salaries in pesos.

Three rates, three privileges, one single lie: that the Cuban exchange system is based on economic criteria.

In reality, it responds to political criteria. And in Cuba, as always, the economy obeys power, not the market.

Filed under: